Empty Houses in New Zealand: A Critical Analysis of the Housing Crisis

Anthonie Van Bosch

9/21/20258 min read

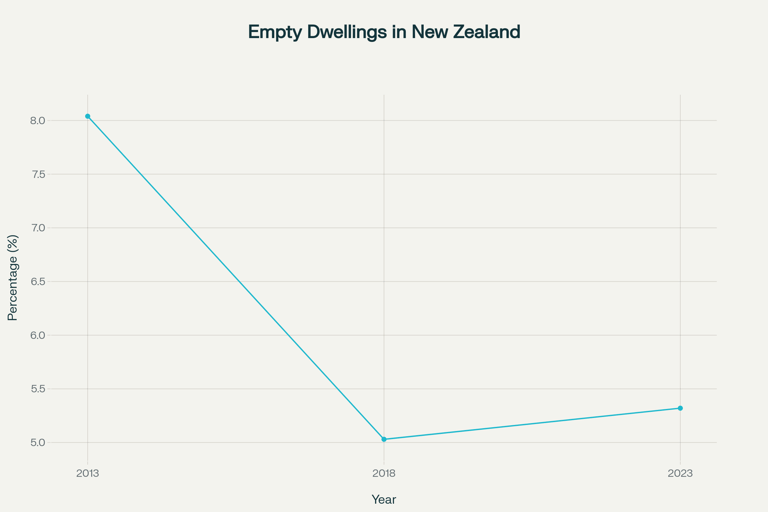

New Zealand faces a substantial challenge with 111,666 empty houses recorded in the 2023 Census, representing 5.32% of the country's total housing stock. This figure has increased from 97,842 empty homes in 2018, marking a significant rise in vacant properties despite the nation's ongoing housing crisis.[1][2]

Scale and Distribution of Empty Houses

The empty housing situation varies dramatically across regions. Auckland alone accounts for 24,228 empty properties (4.1% of its total housing stock), an increase of 7,098 properties (+41.4%) since 2018. The regions most affected by empty properties include:[3]

Highest Empty Property Rates by Area:

- Great Barrier Island: 35.8% (462 empty dwellings)[3]

- Waiheke Island: 12.5% (804 empty dwellings)[3]

- Rodney: 8.9% (2,943 empty dwellings)[3]

- Waitematā: 6.1% (2,739 empty dwellings)[3]

The Tauranga region has seen particularly dramatic increases, with empty homes rising from 1,722 in 2018 to 2,142 in 2023. Similarly, the Bay of Plenty shows concerning trends with Ōpōtiki having the highest percentage of empty homes at 18.2%.[4]

Reasons Behind Empty Properties

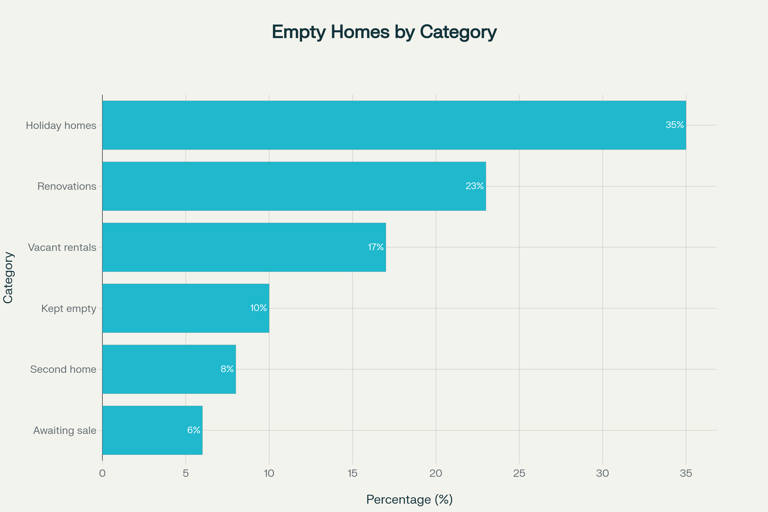

The Empty Homes project, conducted by the Wise Group, provides crucial insight into why properties remain vacant. Their comprehensive analysis reveals distinct categories of empty housing:[5]

Holiday homes represent the largest category at 35% of all empty properties, followed by homes undergoing renovations and repairs (23%), and vacant rental properties (17%). Critically, approximately 10% of empty homes are intentionally kept vacant, representing potential housing stock that could be reintroduced to the market through appropriate interventions.[6][7][5]

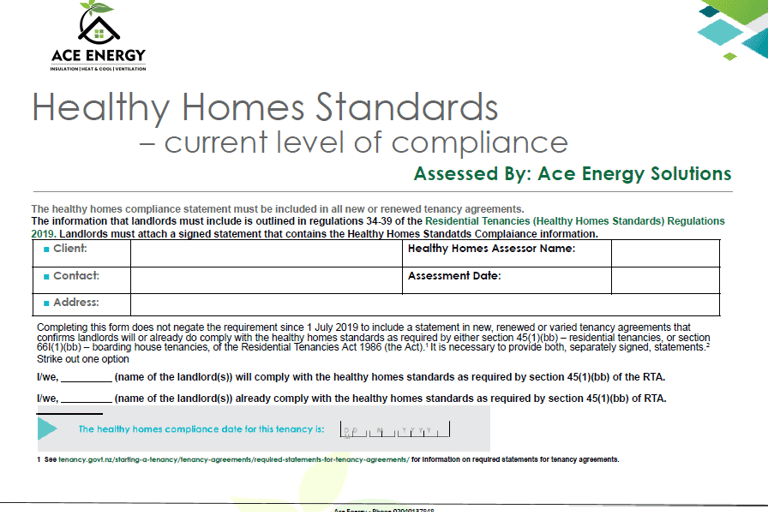

These vacant rentals often result from landlord challenges with Healthy Homes Standards compliance, which requires substantial investment in heating, insulation, ventilation, moisture control, and draught stopping. The compliance burden has led some landlords to exit the rental market entirely, removing properties from circulation despite acute housing demand.[8][9]

Critical Impact on Housing Crisis

The relationship between empty houses and New Zealand's housing crisis is complex but significant. While not all empty properties represent immediately available housing stock, their impact compounds existing supply-demand imbalances:

Housing Affordability Crisis:

- One in four rental households spend more than 40% of disposable income on housing costs[10][6]

- Over 328,300 non-owner-occupied households spend 30% or more of their income on housing[11]

- The housing shortage has driven up both purchase prices and rental costs across most regions

Supply-Demand Dynamics:

Recent analysis shows that housing supply has actually outpaced population growth in major centres like Auckland and Wellington between 2019-2024. Auckland's dwelling stock increased by 10.3% while population grew 7.0%, and Wellington saw dwelling stock increase 4.3% while population declined 1.0%. However, this apparent surplus hasn't translated into improved affordability, suggesting structural market inefficiencies.[12]

The persistence of empty properties alongside housing stress indicates market failures in connecting available housing with those in need. Properties remaining vacant for investment speculation, regulatory avoidance, or inadequate incentives prevent optimal housing utilisation.

Regulatory Challenges and Landlord Response

The current regulatory environment has created unintended consequences that exacerbate the empty housing problem:

Healthy Homes Standards Compliance:

All rental properties must comply with Healthy Homes Standards as of July 2025, requiring landlords to invest significantly in property upgrades. The self-certification system has drawn criticism for placing compliance burden on tenants rather than independent verification. Landlords who fail to meet standards face penalties up to $7,200, creating financial risk that some choose to avoid by removing properties from the rental market.[13][14][8]

Regulatory Burden Impact:

The combination of rising compliance costs, complex tenancy law changes, and negative experiences with problem tenants has prompted smaller "mum-and-dad" investors to exit the rental market. This trend particularly affects properties that would otherwise serve lower-income tenants, reducing affordable housing supply precisely when it's most needed.[9]

Property Manager Challenges:

Over 40% of rental tenancies are now managed by property managers, but this industry remains largely unregulated despite holding significant power over tenants. The professionalisation of property management has created additional costs and bureaucracy that some smaller landlords find prohibitive.[15]

Policy Solutions and Way Forward

Addressing New Zealand's empty housing challenge requires coordinated policy intervention across multiple domains:

Housing Supply Initiatives

Land for Housing Programme:

The government's Land for Housing programme actively acquires vacant Crown and private land for residential development, requiring at least 30% of new homes to be affordable housing, social housing, or progressive home ownership. This programme works with iwi partnerships and demonstrates commitment to increasing supply through strategic land acquisition.[16]

Build-to-Rent Developments:

Emerging build-to-rent developments offer professional rental housing designed for long-term tenancy. While this sector remains small in New Zealand compared to Australia and the UK, it provides an institutional alternative to small-scale landlord investment that may prove more resilient to regulatory changes.[17]

Targeted Empty Home Interventions

HOPE Programme Results:

The Empty Homes project successfully returned 5-7 properties to housing supply during its Hamilton trial, demonstrating proof-of-concept for empty home interventions in New Zealand. The project identified key barriers including landlord concerns about tenant quality, property damage, and regulatory compliance burdens.[5]

Ready to Rent Initiative:

The Ready to Rent programme addresses landlord concerns by preparing potential tenants for the rental market, providing landlord/property manager education, and reducing barriers to successful tenancy relationships. This initiative forms part of the Homelessness Action Plan and could be expanded to support empty home reactivation.[18][19]

Empty House Tax Implementation

Revenue Generation Potential:

Research suggests an empty homes tax could generate $255 million annually using a 3% tax rate on vacant properties. International examples from Vancouver (1% of property value) and Ireland (200-300% of rates) demonstrate workable models, though implementation requires careful design to avoid unintended consequences.[20][21][10]

Structured Tax Design:

An effective empty house tax would need to:

- Target genuine speculation rather than legitimate vacancy reasons

- Provide exemptions for homes under renovation, newly constructed properties, and holiday homes used by families

- Include escalating rates for properties vacant multiple consecutive years

- Generate revenue specifically dedicated to housing supply initiatives

Foreign Investment Policy Reform

Active Investor Plus Exemption:

The recent exemption allowing Active Investor Plus visa holders to purchase properties worth $5 million or more represents a targeted approach that prioritises capital injection without impacting mainstream housing markets. This policy affects only around 10,000 households and excludes over 99% of New Zealand homes from foreign purchase.[22][23]

Market Impact Assessment:

By setting the threshold at $5 million, the exemption targets ultra-luxury property that doesn't compete with housing needed by most New Zealanders. However, this policy requires monitoring to ensure it doesn't facilitate land banking or speculative holding of high-value vacant properties.[24]

Systemic Challenges and Long-term Solutions

Addressing Landlord Market Exit

The trend of small-scale landlords exiting the market due to regulatory burden requires policy recalibration. While tenant protection through Healthy Homes Standards is essential, implementation could include:

- Transition support programmes helping landlords comply with standards rather than exit

- Streamlined compliance processes reducing administrative burden

- Financial assistance schemes for landlords upgrading properties to meet standards

- Professional certification programmes providing landlords with clear compliance pathways

Housing Market Rebalancing

Recent data showing housing supply outpacing demand in major centres suggests the acute shortage phase may be moderating. However, this rebalancing hasn't improved affordability, indicating structural market inefficiencies beyond simple supply-demand mathematics.[25][12]

Market Function Improvements:

- Enhanced rental market transparency through standardised listing requirements

- Professional property management regulation to reduce tenant-landlord friction

- Housing registry systems tracking property utilisation and identifying intervention opportunities

- Improved data collection on genuine housing need versus speculative demand

Conclusion

New Zealand's 111,666 empty houses represent both a significant challenge and substantial opportunity within the broader housing crisis. While not all vacant properties can immediately address housing need, the 10% that are intentionally kept empty – potentially over 11,000 properties – represent lost housing stock that targeted interventions could reactivate.

The way forward requires dual-track action: continuing to increase overall housing supply through construction and development while simultaneously implementing programmes like HOPE and Ready to Rent to overcome barriers preventing vacant properties from serving housing demand. An appropriately designed empty house tax could provide both fiscal incentive for better property utilisation and revenue for new supply initiatives.

Success depends on recognising that empty houses are a symptom of deeper market failures – regulatory complexity that drives landlord exit, speculation incentives that reward land banking, and insufficient support systems connecting available housing with those in need. Policy solutions must address these underlying causes rather than simply penalising vacancy.

The recent easing of supply-demand pressures in major centres provides an opportunity to implement these reforms during a period of relative market stability. By acting now to optimise housing utilisation while continuing supply expansion, New Zealand can build a more efficient and equitable housing system that serves all residents effectively.

[2](https://figure.nz/chart/wOm7YBwPIoRHIjHP)

[4](https://www.1news.co.nz/2024/10/17/the-city-with-2000-ghost-homes-a-hard-problem-to-solve/)

[5](https://www.emptyhomes.co.nz/Content/report/10161%20EH%20Report%20March%202022.pdf)

[6](https://thespinoff.co.nz/politics/05-09-2023/why-investors-should-be-taxed-for-keeping-homes-empty)

[7](https://www.aut.ac.nz/news/stories/why-nz-needs-an-empty-homes-tax)

[8](https://www.tenancy.govt.nz/healthy-homes/healthy-homes-compliance/)

[10](https://b2bnews.co.nz/news/empty-homes-and-the-housing-crisis/)

[11](https://www.stats.govt.nz/reports/housing-in-aotearoa-new-zealand-2025/)

[12](https://www.cotality.com/nz/insights/articles/which-parts-of-nz-are-seeing-supply-outpace-demand)

[15](https://www.consumer.org.nz/articles/the-rise-and-concerns-of-property-managers)

[16](https://www.hud.govt.nz/our-work/land-for-housing)

[21](https://south-thinking.com/blog/empty-homes-taxes)

[24](https://www.minterellison.co.nz/insights/targeted-exception-announced-to-foreign-buyer-ban)

[25](https://www.oneroof.co.nz/news/whatever-happened-to-new-zealands-housing-shortage-crisis-48186)

[26](https://williambuck.com/nz/news/in/property-construction/changes-to-vacant-residential-land-tax/)

[27](https://emptyhomes.co.nz)

[28](https://emptyhomes.co.nz/Numbers)

[30](https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2021-04/tax-housing-4417128.pdf)

[34](http://www.ird.govt.nz/brightline-property-tax-guide)

[37](https://www.branz.co.nz/documents/4364/ER81_Affordable_alternative_housing_tenures.pdf)

[38](https://kaingaora.govt.nz/en_NZ/news/new-approach-to-tenancy-management/)

[39](https://www.propertynz.co.nz/news/in-brief-foreign-buyers-ban-reform)

[40](https://kaingaora.govt.nz/en_NZ/publications/oia-and-proactive-releases/housing-statistics/)

[41](https://tuatahicentre.com/ready-to-rent)

[42](https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2024-06/build-to-rent-4904409.pdf)

[43](https://www.hud.govt.nz/our-work/public-housing-plan)

[44](https://kaingaora.govt.nz/en_NZ/urban-development-and-social-housing/selling-kainga-ora-properties/)

[45](https://thespinoff.co.nz/politics/02-09-2025/new-zealands-foreign-buyer-ban-has-been-binned-kind-of)

[47](https://thehub.sia.govt.nz/sitemap/housing-brokers-and-ready-to-rent-initiatives-process-evaluation)

[48](https://www.tenancy.govt.nz/ending-a-tenancy/change-of-landlord-or-tenant/change-of-landlord/)

[50](https://www.regulation.govt.nz/assets/RIS-Documents/ria-hud-rtacct-nov22.pdf)

[53](https://mccawlewis.co.nz/publications/healthy-homes-standards-who-is-complying/)

[54](https://www.tenancy.govt.nz/rent-bond-and-bills/market-rent/)

[55](https://www.consumer.org.nz/articles/home-improvements-the-healthy-homes-standards-five-years-on)

[57](https://www.hud.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Documents/Regulatory-Impact-Statement-Amendments-HHS.pdf)

[58](https://aspireproperty.co.nz/rental-market-update-january-2025-law-changes-and-data-to-help-you-with-your-next-property-purchase/)Blog post description.